“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

—Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

NOTE: This article is a precursor to an upcoming three article series examining Rey’s Hero’s Journey in The Force Awakens.

———————

While writing the original drafts of Star Wars in the early 1970s, George Lucas came across the works of Professor Joseph Campbell. Campbell’s ideas of universal mythical themes found within the stories of every society helped Lucas focus his intention of making a mythological story of good verses evil for the modern world (especially for children) and imbued his screenwriting with themes and characters that would resonate deeply within his audience.

Lucas later met Campbell (whom he called “my Yoda”) in 1984 and the two became friends. In 1987 a PBS interview series with Campbell, The Power of Myth, was filmed at Lucas’s Skywalker Ranch shortly before Campbell passed away. This popular series brought Campbell and his works to a larger audience, and re-airings of the programs in the 90’s served as my own introduction to him.

In 1949, Joseph Campbell (1904-1987) published a book on comparative mythology called The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In this work, which expanded on the theories of psychoanalysts and anthropologists such as Sigmund Freud, C. G. Jung, Max Müller, and Arnold Van Gennep, Campbell compared various religions, myths, and fairy tales from around the world, and he showed—while acknowledging the existence of unique qualities of time and place—they all contained at their heart similar themes and character types that could be mapped out into a kind of universal story pattern. This pattern—which mirrors the human psychological experience from birth to death—can be found in virtually every story. Campbell called this pattern the Monomyth, a term borrowed from the work of Campbell’s favorite author, James Joyce. The pattern is more widely known as The Hero’s Journey.

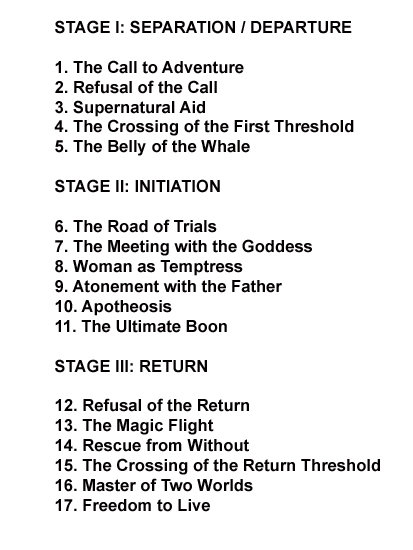

Campbell’s Outline of The Hero’s Journey

Campbell breaks down the Journey into three “stages” representing the three stages of the Rites of Passage (initiation rituals representing the passage from one sphere of life to another, e.g. child to adult), drawn from Van Gennep’s book of the same name, with seventeen “subsections,” which I will call “steps.” I won’t elaborate on the meaning of each step here as I will be using a different version of the Journey, as explained later.

In 1985, Hollywood story consultant Christopher Vogler (working at the time for Disney) explored the Monomyth in a company memo titled A Practical Guide to The Hero with a Thousand Faces. This memo attempted to convey Campbell’s ideas in a distilled, modern form geared towards screenwriting and using the three-act structure in place of the three stages of the Rites of Passage. Vogler’s form of The Hero’s Journey was then unitized in the development of Disney films, including The Lion King. This original memo can read online for free at Vogler’s website.

The memo also made its way outside the company and became popular throughout Hollywood. Vogler eventually expanded on the memo in his 1992 book The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Storytellers and Screenwriters. (which was greatly expanded on in the 2007 3rd edition, by then re-subtitled Mythic Structure for Writers). Vogler showed the flexibility and adaptability of the Monomyth for modern storytelling, using examples from Thelma and Louise to Erin Brockovich to Pulp Fiction.

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell himself said of the variations of the Journey, “The changes rung on the simple scale of the monomyth defy description. Many tales isolate and greatly enlarge upon one or two of the typical elements of the full cycle… others string a number of independent cycles into a single series (as in the Odyssey). Differing characters or episodes can become fused, or a single element can reduplicate itself and reappear under many changes.”

While stories don’t have to rigidly adhere to classic stereotypes in order to fit the archetype of the Journey (such as the lowly farm boy learning of his heroic destiny from a wise old wizard), the Star Wars saga was partially designed as a retelling of classic mythological motifs, and so it uses a more classical “skin” over the framework of the Monomyth.

Below is Vogler’s outline of The Hero’s Journey with my own explanations of the steps and examples from the complete Journeys of Luke and Anakin.

ACT I – SEPARATION / DEPARTURE

- The Ordinary World: The starting point of the hero, which is contrasted with the Special World of the Adventure. Here we are shown the circumstances of the everyday life of the hero, in which the hero may be naively comfortable or desirous of change. It can be a specific location and/or a frame of mind. Anakin as a slave, wanting to be free and gain the power to bring freedom to others. Luke as a farm boy desiring to break free of his mundane life and be more than he is.

- The Call to Adventure: Something is introduced into the hero’s life which calls for them to take action and/or change their outlook. This can be an outside force or opportunity (good or bad) or something within the hero that prompts them to change their current path. There are usually Inner Problems (personal flaw or moral dilemma) and Outer Problems (the outward plot dilemma) to be faced. The call from Qui-Gon to Anakin to become a Jedi and fulfill the Chosen One prophecy. Outer Problem of becoming a Jedi, Inner Problem of facing the fear and anger of possibly losing his mother. The call for aid from Leia and the call from Obi-Wan to be a Jedi. Outer Problem of helping the Rebellion fight the evil Empire, Inner Problem of actually leaving his comfort zone to take on a real adventure, and, later in his journey, doing so without succumbing to the dark side.

- Refusal of the Call: Some heroes refuse this call due to fear and/or pressures from family or society, but fate ultimately pushes the hero back onto the path. Anakin is very eager to become a Jedi and fulfill his dreams, but he has a moment of hesitation when he realizes he may never see his mother again. It takes the gentle assurance of Shmi for Anakin to turn away from his mother and follow the path of the Jedi, a choice that comes to haunt him and the galaxy. Luke talks big about wanting to leave Tatooine, but when the chance for real adventure presents itself, he uses the excuse of his responsibilities on the farm. It takes the death of his aunt and uncle at the hands of the Empire to push Luke onto the path.

- Meeting with the Mentor: At some point early in the adventure, the hero usually comes into contact with one or more wise characters who are able to give them guidance, wisdom, training and/or equipment for their journey. Sometimes a Mentor is also the Herald who issues the Call. The Mentor can often be found in a guise belying their true power, like the crazy old wizard, Ben Kenobi, or Yoda pretending to be an annoying little creature to test Luke’s maturity and perception. Anakin sees through Qui-Gon’s disguise, though his ideals of what a Jedi should be (he initially believes Qui-Gon is there to free the slaves) are not straightway fulfilled. On the dark side, the kindly Senator Palpatine hides the true dark side power of Darth Sidious as he mentors the young and naive Anakin.

- Crossing the First Threshold: The point at which the hero moves across the border between the Ordinary World and the unfamiliar realm of the Special World (which can be a new physical space or simply a new experience). It is the start of the Adventure in earnest. At the threshold there are usually Threshold Guardians who stand watch at the gate. These must be overcome through force, trickery, or winning over. Anakin passes the Guardians of slave master Watto and Darth Maul with the aid of Qui-Gon and enters the cold of space, then on to Coruscant to be tested by the Jedi Council. Luke, through the aid of Obi-Wan’s Force powers, passes the stormtrooper Guardians as they enter Mos Eisley.

ACT II – INITIATION

- Tests, Allies and Enemies: In the Special World, the hero now faces various trials, meets or strengthens ties with allies, and comes into deadlier conflict with new or existing enemies. Anakin is tested before the Jedi Council, where the seeds of his animosity towards the leaders of the Jedi begins. He also draws the attention of Palpatine. In Episode 2, he must face trials of emotion as his frustration with the Jedi Council grows, as does his love for Padme. His ties to the light side are greatly tested with the death of his mother. Luke makes many allies and enemies along his path, and his trials with Yoda in Episode 5 deepen his understanding of the Force and what it means to be a true Jedi.

- The Approach: Here the hero prepares (knowingly or not) for the greater danger to come, often gathering the resources (physical and psychological) needed to face their ultimate Ordeal. In Episode 2, Anakin and Padme have a tentative flirtation and rejection period (approaching the Ordeal of their relationship) before giving themselves over to their fateful love and binding through marriage. Luke is tested in the dark side cave. Not heeding the advice of his mentor, he takes his weapons with him, faces an apparition of Vader, and sees his own face beneath the mask.

- The Ordeal: The hero now comes to face death. This is usually the place where the object of the quest is kept, where the most powerful guardians (including one’s own fears) must be faced. There is typically a sacrifice made where the hero or an ally of the hero dies or is seriously wounded. In Episode 3, Anakin fails his Ordeal and succumbs to the dark side with the false promise of saving his wife. In Episode 5, Luke faces Vader, loses a hand, and has the shocking reveal that Vader is his father.

- The Reward/Seizing the Sword: The hero, having faced death and survived, finds their reward (physical and/or spiritual). This is a victory, but more danger is usually awaiting the hero’s departure. Anakin earns the “reward” of power and control over the galaxy through the dark side and becomes the right hand of the new Emperor, but he is also punished with the lose of his wife due to his own actions. Luke, having learned the truth about his father and sensing the good left within him, finds the reward of hope that he could bring Anakin back from the dark side.

ACT III – RETURN

- The Road Back: As the hero flees the place of the Ordeal, they are pursued by the enemy, who is angered at their victory. This is often portrayed as a literal chase scene, but can also be a psychological flight and pursuit. Luke is spiritually “pursued” by the dark side through Vader and the Emperor. He must flee from these temptations if he is to save his father and the galaxy. In Episode 6, Vader is reminded by Luke of who he once was, beginning his road back to the light.

- The Resurrection: The hero faces their final test where all they have learned must be used to survive. This is another moment of death and rebirth where the hero reaches their highest level yet. Luke refuses to kill his father, breaking through the temptation of death within the dark side. He is reborn as a Jedi like his father before him (an identification with the good that was once—and could still be—in Anakin and a rejection of the fallen Vader). Though Vader he is mortally wounded in destroying his former master, he is resurrected as Anakin by the example of selfless love through his son. The inhuman machine mask is removed—literally and figuratively—and the fragile human within is revealed.

- Return with the Elixir: With the (possibly only temporary) defeat of their foe, the hero resolves the conflicts of the adventure, at least for now, and may take what they have learned back with them in their new life (possibly back to their Ordinary World). This usually comes as a benefit to their society as a whole. The ultimate heroes do not keep what they have learned to themselves, but teach others, becoming mentors themselves. Luke, having saved Anakin with the Elixir of a son’s unconditional love for his father, he ends his journey with the promise of teaching what he has learned to a new generation of Jedi Knights. Anakin, having fulfilled his destiny as the Chosen One, now becomes one with the Force, appearing beside his old mentors and becoming a potential guiding influence on future generations of Jedi.

THE ARCHETYPES

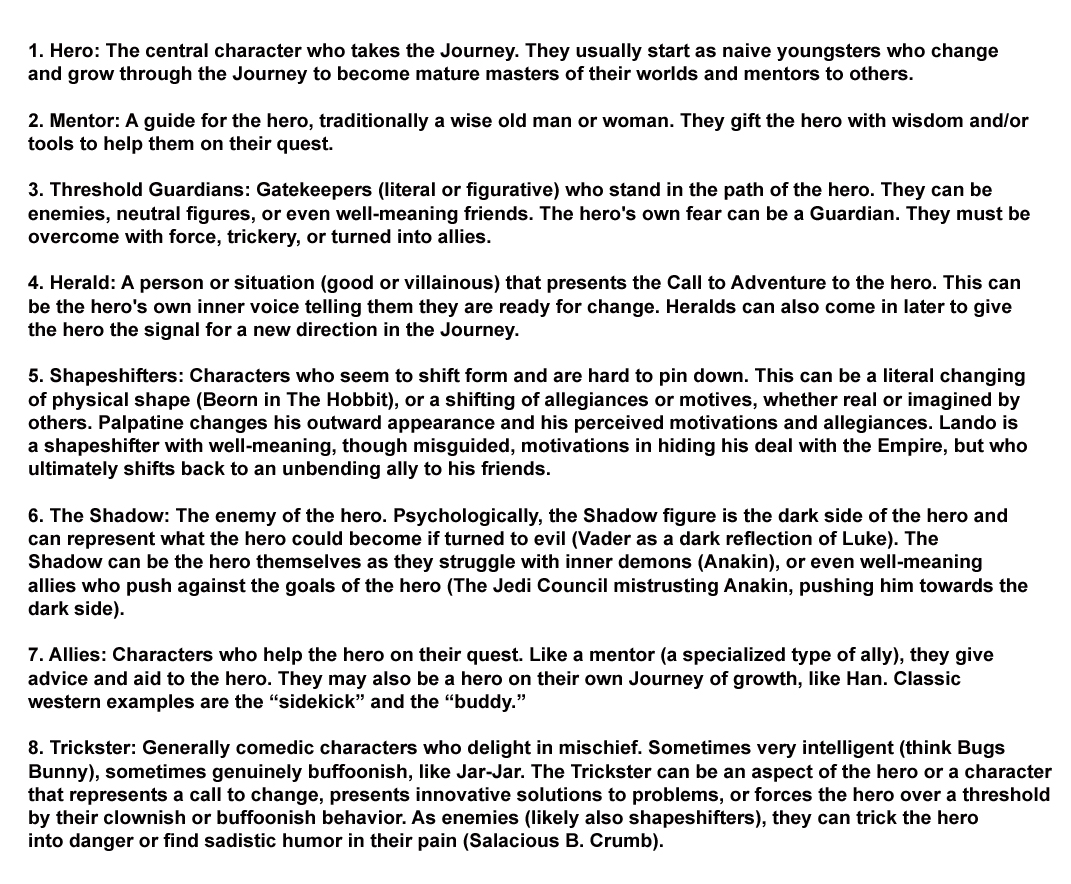

Along with the Hero’s Journey, Vogler emphasizes (to a greater degree than Campbell) eight archetypes, “recurring patters of human behavior, symbolized by standard types of characters.” The Archetypes were taken from C. G. Jung, who built on the work of others in formulating them.

It needs to be noted that the archetypes are not rigid roles that are locked into place, but “masks” or “functions” that can be worn and discarded by any number of characters within a story.

Vogler’s 8 Archetypes with my own descriptions

To be continued in Rey: On the Hero’s Path – Part 1

Sources

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973. Print.

Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth. PBS, 1988. DVD.

Larsen, Stephen, and Robin Larsen. Joseph Campbell: A Fire in the Mind: The Authorized Biography. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2002. Print.

Vogler, Christopher. “The Memo That Started It All.” Storytech Literary Consulting. GODADDY(dot)COM, LLC, n.d. Web. 11 July 2016.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 3rd ed. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2007. Print.

[…] here for Part 1 and here for a history and introduction to the Hero’s […]

[…] HERE for Part 1, HERE for Part 2, and HERE for a History and Introduction to the Hero’s […]

[…] NOTE: For a history and breakdown of the Hero’s Journey concept see my prologue article, The Hero’s Path. […]